The history of Makahiki reveals a deep meaning tied to rituals, prayers, and religious activities honoring the Hawaiian god Lono.

“Makahiki is a time to harvest, but it’s not about harvest,” says Kapaliku Maile, Bishop Museum education programs manager. “Games are played, but it’s not about games. It’s actually a time to reset and to reframe the priorities of the day to ensure that Lono is being respected.”

The celebration of Makahiki that started last fall ends in early January this year, according to the Bishop Museum’s calculations. During this annual event, communities gather and play games to celebrate the Hawaiian new year.

Rituals, prayers, and religious actions were the major focus of Makahiki.

Maile says the historical record of Makahiki differs from island to island. “Most of what’s known is related to practices from Kamehameha’s time, whereas before unification, different islands had different rituals.”

The start of Makahiki depends on which kaulana mahina (Hawaiian lunar calendar) is used. “There are many different kaulana mahina recorded from the historical period, which involve different islands and specific sites on each island.”

Bishop Museum relies on calculations based on David Malo’s recording of Makahiki rituals and traditions. According to the kaulana mahina that Malo uses, the month of Ikuwa runs from late September to late October and the month of Kaelo is late December to late January. Makahiki begins on the 13th day of Ikuwa and ends on the 14th day of Kaelo.

Maile says expertise is needed to read the signs in the sky that reveal the start of Makahiki.

“The appearance of Makalii (Pleiades) is contextualized by other signs and being able to read these signs from a specific place so that calculations and observations are consistent,” he says. “These observations are done by specific kahuna (priestly experts) and the reading of these signs can determine the actions of the chiefs and nonranking people for the year.”

These actions include two important ceremonies: Kauluwela, marking the end of one year and the transition from the Ku (god of war) season to the Lono (god of peace and fertility) season, and Kuapola, which was conducted in two parts.

“High chiefs and high priests conduct the Kuapola ceremony of Ikuwa to set intentions for the year,” Maile says. In the Kuapola ceremony in the month of Welehu (the first month of the Hawaiian lunar calendar), observations and prognostications from the first ceremony are relayed to the entire community.

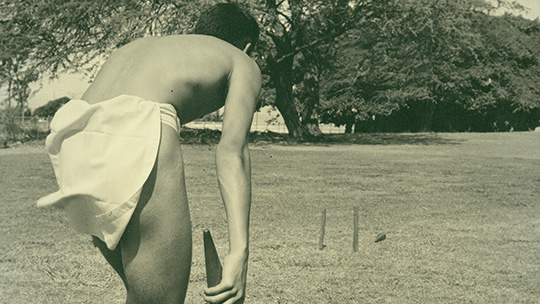

Moa pahee, or dart sliding, is still played during Makahiki today.

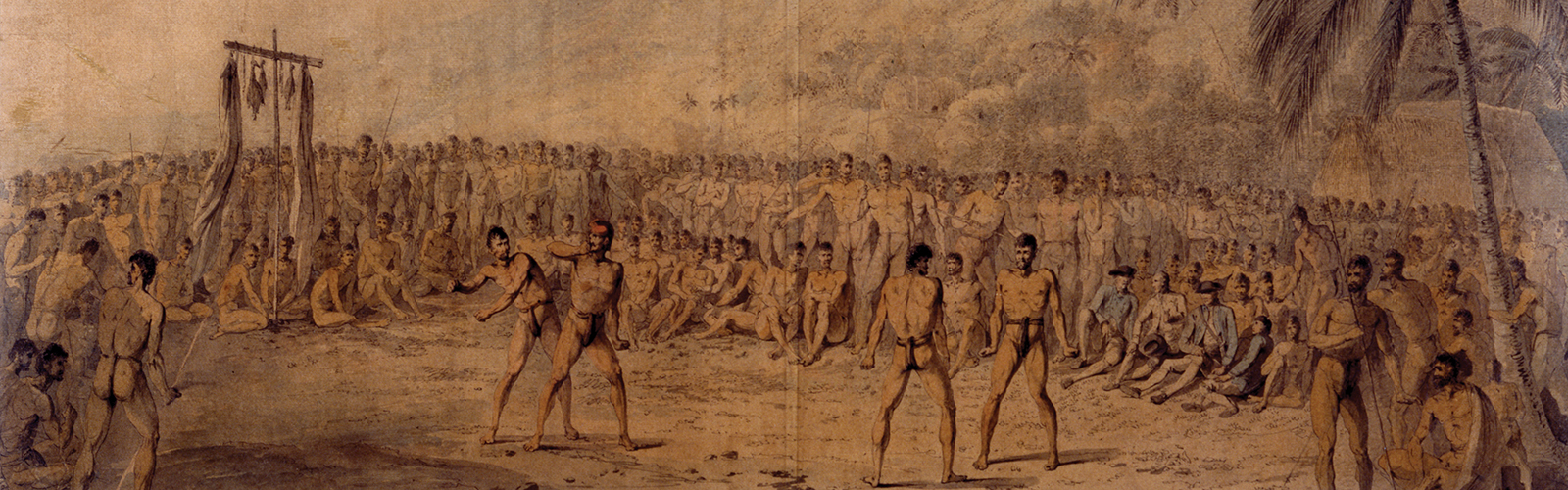

The history of Makahiki includes games and other activities, Maile says. “Mokomoko (hand-to-hand fighting, wrestling, and/or boxing) was specifically conducted during Makahiki periods once the major rituals, prayers, and religious actions were completed successfully,” he says. “Other games like ulu maika were also played by the makaainana (common people), although high chiefs were not necessarily part of games and physical activities until the important rituals were concluded. Hula was also seen as part of Makahiki practices later in the season during other celebratory rituals.”

Makahiki celebrations are different today but serve as a significant nod to the past.

“Makahiki is an endearing, enduring tradition,” says Maile. “And its resilience is one that’s mirrored by the Native Hawaiian community today because they’re the folks who are keeping those things going.”

Photos courtesy of Biship Museum.