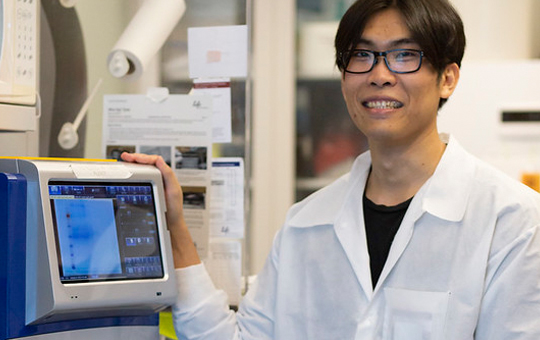

Albert To was looking forward to graduating from the University of Hawaii at Manoa this spring with a doctorate in tropical medicine. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, putting his plans on hold.

He was on a path to doing a post-doctorate program on the Mainland. But as the pandemic began spreading throughout the U.S., there was a greater need for him to stay in Hawaii. While Mainland research laboratories shut down at the start of the pandemic, UH’s lab remained open, giving him a jump-start on working on a COVID-19 vaccine.

“It’s a calling,” To says. “This is what I’ve been preparing for. We’re going full force on the COVID-19 vaccine. It’s been a lot of late nights and early mornings in the lab."

To is among a dozen UH scientists working on a COVID-19 vaccine at the Department of Tropical Medicine and Microbiology at the John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM) in Kakaako. He’s the most experienced among the student researchers. In 2016, he worked on creating a vaccine for the Zika virus and has worked on UH’s ongoing Ebola vaccine project. Those experiences helped him produce an antigen that would generate a robust immune response to protect against COVID-19.

“Albert is the right person for this job,” says Axel Lehrer, a JABSOM associate professor who's leading the UH vaccine project.

The UH team is currently testing their vaccine on animals. Although many vaccine candidates nationwide are being tested in human clinical trials, the Hawaii scientists don’t want to rush their process. “We want to make sure our vaccine is both effective and safe,” says To, a graduate of Roosevelt High School. “If it cannot protect mice or monkeys, it cannot protect people.”

There are about 200 COVID-19 vaccine candidates in development worldwide. One of the obstacles for the Hawaii scientists has been funding. They don’t have the same financial resources as large national pharmaceutical companies. Still, they’re confident in their ability to produce a thermostable vaccine that can be used anywhere in the world.

“We’ve done our homework and are working at a faster pace than the typical 15 to 20 years it takes for a vaccine. We’re doing the best we can with the resources we have to be in the race,” he says.

Even if Hawaii isn’t the first to develop a vaccine, the need is so great that multiple vaccines may be needed for global use. To would like to stay at UH until a vaccine is found, but he’s still looking at other opportunities on the Mainland.

“The need is now,” says To. “I’m just grateful to make a contribution.”

Photos courtesy JABSOM